Why Teens Across the Country Are Acquiring Brooklyn Public Library’s Free Digital Cards: Book Censorship News, September 20, 2024

New York’s Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) has been among the most active library systems in addressing the book censorship crisis across America. In 2022, BPL launched its Books Unbanned program. Among the many pieces of the program is its extension of digital library cards to anyone between the ages of 13 and 21 in the US. This grants young people access to its vast digital collection, including the kinds of books that are being banned nationwide. BPL’s program has extended to include several other libraries since its launch.

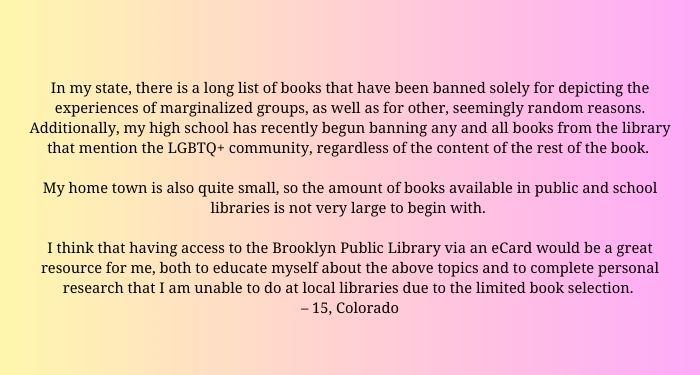

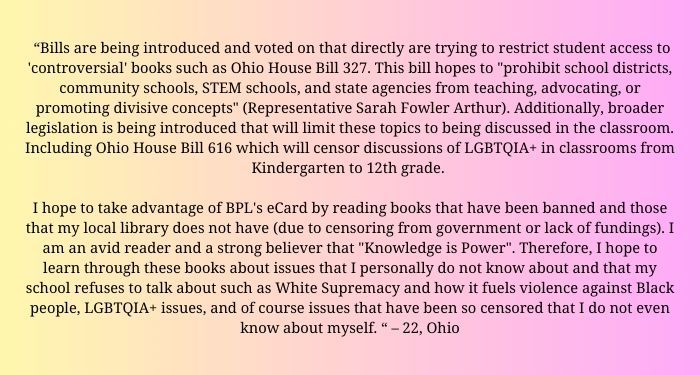

As part of the program, BPL asked applicants to share why it is they wished to get a card. In the first year of the program, April 2022-2023, teens who wanted a card would email and receive an autoresponse which allowed them to respond with their stories and experiences. In the second year of the program, April 2023-2024, continued requests for cards, as well as renewals of the cards issued in that first year, prompted BPL to create a form that collected information from teens to get the card, as well as a free form text box where they could share their stories. In both scenarios, teens indicated whether or not those stories could be shared publicly, with identifying information removed.

BPL had a lot of data.

In conjunction with partner library Seattle Public Library, BPL offered students at the University of Washington’s Information School a capstone opportunity: organize the data. Four took up the task, beginning with a sampling of 855 stories. Their work involved categorizing the submitted stories, including reasons teens indicated they wanted a card, what barriers to access they were experiencing, and what kind of book censorship they were experiencing in their communities.

Though 855 stories gave a sense of what was happening nationwide in terms of library access and book banning, there were still thousands more stories to catalog. BPL invited the four new graduates to continue their work. In early September 2024, they finished cataloging the first two years’ worth of stories from teens who voluntarily shared their experiences when applying for or renewing their Brooklyn Public Library eCards.

The data and stories that have been cataloged were shared by teens between April 2022 and April 2024 and focus exclusively on BPL ecard sign-ups (so it does not include partner libraries in the program that also offer eCards). BPL has tagged and organized roughly 4,500 stories from Books Unbanned cardholders, which represents a fraction of the total number of teens who have acquired the cards. Given the size of the data pool, what you’ll see below is likely strongly representative of the thousands of stories that have not been shared. BPL is still collecting these stories, with plans to continue organizing them and with plans to expand the project to partner libraries.

Here’s what two years’ worth of teen stories show about the state of libraries and book bans in the US.

Where Are These Stories Coming From?

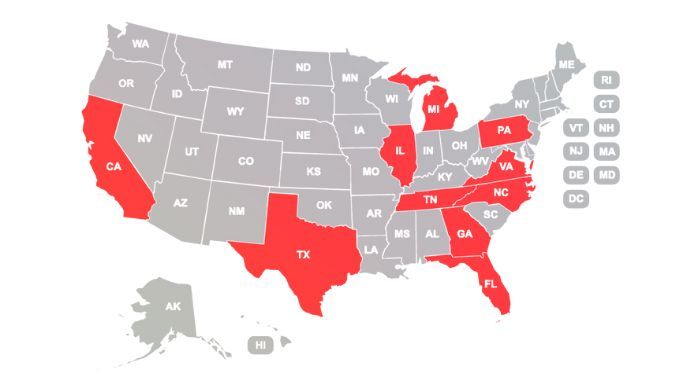

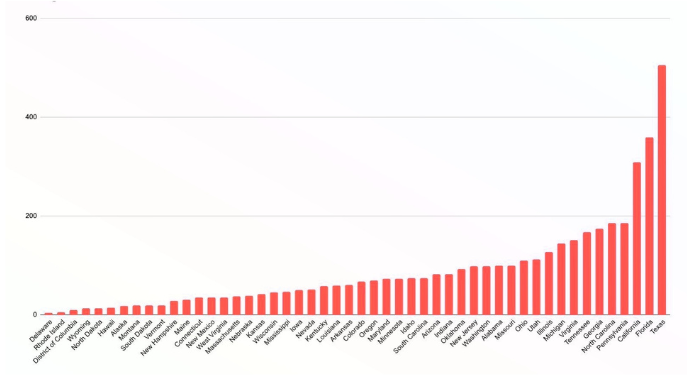

Digital cards have been registered in every US state—minus New York, where access to such cards is not a new initiative—as well as the US territories of Puerto Rico and Guam. The top 10 states from which teens shared their stories, in descending order, are: Texas, Florida, California, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, Michigan, and Illinois. While it is true that many of these states are among the top when it comes to book banning, others are not. California and Illinois, for example, are not among the biggest banners; indeed, what that suggests is teen access to library collections may be hindered in other ways.

This chart is a little difficult to read, but you can make it bigger and check out the distribution by US state. Again, New York is not included. Puerto Rico and Guam are not included either, but Puerto Rico had eight sign-ups and Guam, one.

The cities with the most eCard sign-up stories shared by teens in descending order were:

- Las Vegas, Nevada

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Houston, Texas

- Austin, Texas

- Boise, Idaho

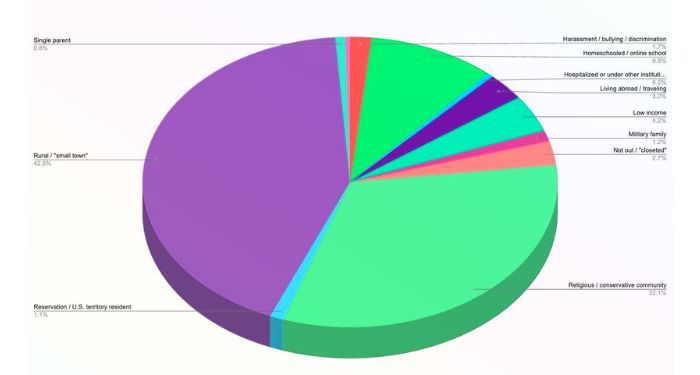

Why Teens Wanted a BPL eCard

What circumstances prompted an interest by young people in getting an eCard? When the catalogers read through the initial set of data, they found 12 categories. Some of the data fit more than one category, so some were included in multiple.

In descending order, teens cited the following reasons for requesting an eCard:

- Rural / “small town”

- Religious / conservative community

- Homeschooled / online school

- Low income

- Living abroad / traveling

- Not out / “closeted”

- Harassment / bullying / discrimination

- Military family

- Reservation / US territory resident

- Single parent

- Hospitalized or under other institutional confinement or care

- Unhoused / unstable housing

This data is important because not only does it showcase the importance of access in situations of censorship, but also the ways that public libraries are still inaccessible to many who may live in rural areas or live in communities where those libraries have limited collections or hours. For example, one of the communities with a number of BPL eCard holders in Illinois has a library that is only open five days a week, Monday-Thursday and Saturday between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m., with an hour between 1 and 2 p.m. where it is closed. It is a rural community and likely has a tiny staff. The data is also a reminder that when a book is removed from shelves, access to that material is not easy for young people. They may not have a school library or a public library to use if a book is removed from one or the other, just as they may not have transportation to get to the library. Teens do not have the cash to purchase materials, were there to be a bookstore in their town or nearby, and most do not have credit cards to purchase the material online if they did have the money.

Additionally, BPL’s card has extended access to those in unstable housing situations, who may move due to travel or work assignments, and those who participate in home or online school.

Then there’s the reality that some teens need digital access to materials—it is crucial, especially for those with disabilities that requires them to use electronic material, including audiobooks. In many libraries, including larger suburban ones, the budget for digital collections can be tight and with a rise in demand for these formats, acquiring more items or expanding that access can be a real challenge. BPL’s card provides a robust collection that may simply not exist for many.

BPL’s card also helps teens who find themselves in the precarious position of either not being out to their families or living in families where their identities are not supported or embraced (not to mention that, especially in smaller towns, familial support might not matter if the community itself is not welcoming). The privacy young people have to peruse and borrow digital material from the BPL collection is crucial. Despite the knee-jerk reaction some “parental rights” activists might have about this, as has been emphasized over the last four years during this current rise in book censorship, none of the materials that are available in public libraries or school libraries are pornographic nor obscene. Instead, BPL’s digital access provides teens the opportunity to read age-appropriate, professionally vetted materials that cover sensitive and deeply personal topics in a safe manner.

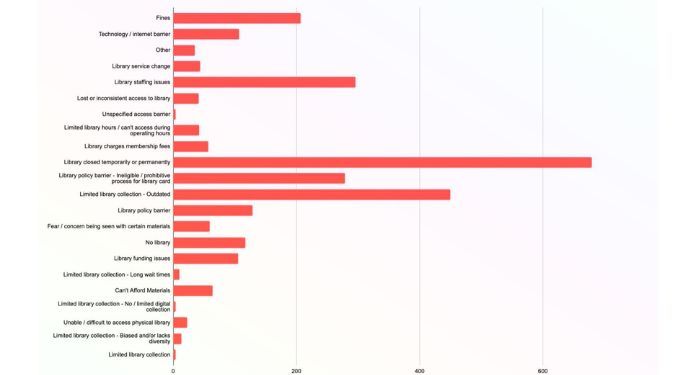

Cardholders shared the barriers to access they faced. Like with the circumstances question, the team tagging the stories read through each story and developed a taxonomy that allowed them to sort the responses into 22 categories. Stories could be categorized within more than one option. For the sake of ease below, “Unspecified” as an option was only counted if no other options were selected.

The barriers to access in descending order from most to least were:

- Limited library collection

- Limited library collection — Biased and/or lacks diversity

- Unable / difficult to access physical library

- Limited library collection — No / limited digital collection

- Can’t Afford Materials

- Limited library collection — Long wait times

- Library funding issues

- No library

- Fear / concern being seen with certain materials

- Library policy barrier

- Limited library collection — Outdated

- Library policy barrier — Ineligible / prohibitive process for library card

- Library closed temporarily or permanently

- Library charges membership fees

- Limited library hours / can’t access during operating hours

- Unspecified access barrier

- Lost or inconsistent access to library

- Library staffing issues

- Library service change

- Other

- Technology / internet barrier

- Fines

Note that the least common response was due to fines, but the most common responses related to challenges of access, including to a broad range of materials and to the library itself.

BPL has been one of the leaders in researching the policies that libraries have across the nation when it comes to card sign-ups. The teen data adds to their ongoing work about the ways libraries can make access to their facilities and materials more equitable. Even in 2024, it can be difficult to sign up for a library card in some places, be it because of residency requirements, language barriers, age restrictions, or other reasons.

Teen Reports on Local Book Bans

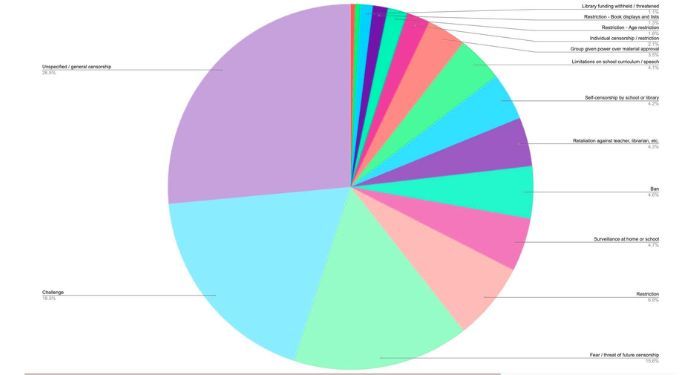

About half of the teens over the two years of analyzed data shared stories of book bans in their local area. Information shared included the type of censorship, the source of that censorship, and the subjects of the banned books—a few included the specific books as well.

The researchers synthesized the stories into 19 categories for the type of censorship reported. Many stories fit into more than one category. These included “unspecified/general censorship,” which was sometimes selected in conjunction with other reasons; in the data below, the responses count only those who responded with that selection. Likewise, “Ban” was used as a category in addition to three others, “Ban — wholesale ban,” “Ban — unauthorized book removal,” and “Ban — refuse to add certain materials.” Those three have been collapsed within the bigger category of “Ban” below, as they not only make up a small number of responses but they were frequently selected in addition to “Ban.”

The top five reasons were Unspecified/General censorship, a Challenge, Fear or threat of future censorship, Restriction, and Surveillance at home or school.

Nearly 2300 responses also mentioned where the source of censorship in their community was coming from. That information was organized into 12 categories and stories often fit more than one. The list, from most common to least:

- Unknown or unspecified (with no other choice indicated)

- School / library board or administration

- Legislation

- Community pressure

- Elected / public official

- Parent(s) or other family member (of cardholder)

- Advocacy / censorship group

- Church / religious group

- Librarian / library worker

- Teacher

- Non-legislative government intervention

- Other (only 2 selected this)

Two times the number of teens did not indicate from where the censorship was stemming compared to those who did. But the most common answers make one thing clear—this isn’t happening in secret. Teens know the decisions to ban books are coming from within the school house, as well as from sweeping legislation.

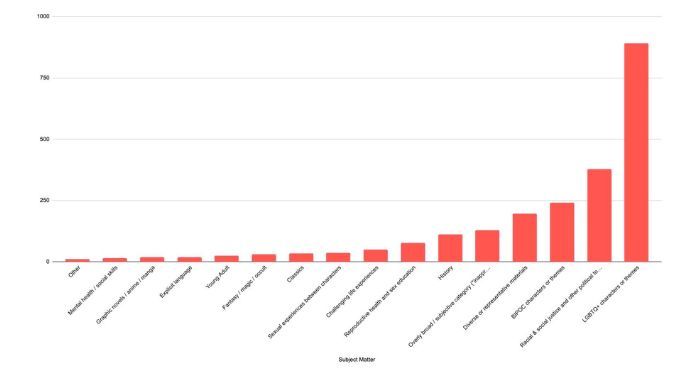

Last but not least, about half of those who reported local censorship provided insight into the type of content seeing bans and restrictions. That amounted to over 1300 responses. It will come as no surprise that the responses mirror the things that freedom to read advocates already know and have drawn attention to again and again. The researchers organized that data into several categories and more than one category could apply to each story.

The top five themes in banned books as reported by the teens? LGBTQ+ characters or themes, Racial & social justice and other political topics, BIPOC characters or themes, Diverse or representative materials, and Overly broad / subjective category (“inappropriate”). All of those answers further explain the teens’ responses about wanting a BPL eCard because it would provide them a more diverse, inclusive collection than is available to them.

What the Teens Are Saying

Banned Books Week is not about marketing Banned Books Week. This isn’t a celebration, nor should it be. Banned Books Week is about encouraging action and advocacy all year long to ensure that all people have the right to read. As you witness banned books displays that feature only the classics, or you hear about the free books being distributed in majority-blue cities, remember that those are marketing, not what’s actually happening.

What’s actually happening is best addressed by those personally affected by today’s rise in book censorship: the teens.

Find below an array of testimonials from the young people who’ve acquired free eCards from Brooklyn Public Library. You can find more by going to the landing page for Books Unbanned, and encourage the young people in your life to sign up for a card, too. They can apply not only for the one at BPL, but those made available through partner libraries as well—every library catalog is a little different, so this level of access is not only unprecedented but a powerful way to help young people who want nothing more than to read about people who look like them—and those who don’t look like them. In addition to the stories shared below, take the time to read through the April 2024 report compiled from the first round of cataloging the teens’ stories. These stories aren’t going to go away. If anything, we’re going to see more and more stories like this as book bans continue to rage nationwide.

BPL cards are a bandaid on a gaping wound, but it is a bandaid offering the kind of support and broad reach that so many others cannot or are not. It has also provided the kind of data showing the broad range of barriers young people have when it comes to borrowing and reading books that they are interested in.

- “I grew up in a religious and conservative family. A lot of things I was taught and then never allowed to question. Of course, as I got older, I began to question things I once believed, and over time, began to read about the questions adults wouldn’t answer for me. And as I’ve grown older, it’s gotten simultaneously easier and harder. People are aware of the pushback against books that speak plainly about issues or overt allegories, but that doesn’t mean that they’ve gotten easier to access. Of course pirating exists, and I cannot say I’ve never pirated anything, but I try to support authors and libraries where I can, and that has grown difficult in the years passing. It’s so much easier to accidentally stumble across something that leads more into propaganda for capitalism and our current way of life than it is to deliberately find something of actual meaning that speaks against it.” —19, Utah

- “The library here is very small and doesn’t carry a lot of the books I’m interested in reading. Some them being classics that I’m aware use to be required reading books. I’m trying to learn more about the LGTB community and wanting read books better understand the issues faced being in this community. We don’t have if those kind of books in our library. I have friends I’d like to read these books as well.” —13, Louisiana

- “As a nonbinary teen living in South Carolina, I have trouble finding books with strong LGBTQ+ characters. Although there are some books like this in my public library, there are none in my school library. It’s financially difficult for my family to visit the public library due to gas and other fees, and I have a Kobo eReader that I adore and would love to use to read books that relate to me and my story. There are also other miscellaneous censorships that are still a concern, but I find that this is the strongest issue that I look for in my libraries.” — 13, South Carolina

- “I’ve always seen stories as a sort of expression of oneself. I’m a writer myself, and it’s nice to be able to create a story where you can add whatever, even if it’s controversial. Sometimes, people write because they can’t find stories that tell their story, if that makes sense. If you’re anything other than white, cishet, neurotypical (and so on), it’s suddenly unacceptable to society. Of course, reading the same sort of perspective gets tiring after a while. I’m queer and neurodivergent myself, and I have a few Asian American friends, and it’s hard sometimes to find books where the main character is Asian, or if they’re transgender, because some people have deemed these books ‘inappropriate.’” — 14, California

- “I am a genderqueer teen from central Louisiana. I have been trying to find some LGBTQIA+ representation in the books I read as well as trying to learn a bit more about CRT and other topics that the school library and public libraries seem to not have. They won’t specifically say that books on these topics or books with “deviant sexual morals” (as they refer to nonheteronormativy) are specifically banned. But they will simply say that they do not carry these books. My mother is trying to include banned books as part of my out of school education, but we do not have the money to actually go out and purchase them.” — Louisiana

- “I almost wrote that I’d be happy to answer your question. But I’m not. I live in Ohio where politicians have written up a SUPER sucky bill that will make it illegal for teachers to even mention “divisive” topics in school. They made a list of topics including “systemic racism”, “CRT”, and ANYTHING having to do with LGBTQIA anything. The SUPER sucky bill has already given a LOT of grown ups the courage to get more books banned from school classes and libraries than they have tried to in a long time. They haven’t gotten ALL the ones that wanted banned banned but they have gotten some through! And if it passes I bet there will be even more. Like most kids, the school library is the one I have easy access to so if they take a book away it’s hard to get!” — 15, Ohio

- “I attend a christian private school with christian conservative parents and have little access to books due to living off of their financial aid alone. I would love access to your collection of audiobooks so i could add to my yearly reads and expand my knowledge of topics that I otherwise can’t learn about through school or knowledgeable friends.” — 17, North Carolina

- “I grew up in a conservative town in Texas, so there wasn’t any books including LGBTQ representation. As a nonbinary transgender 14yo, it was hard to grow up and not be able to see myself in the books I read. I loved to read, but eventually I became frustrated by the lack of representation and stopped. My school library also wasn’t allowed to have books that weren’t approved. Many parents would become upset if they thought their children were being influenced by something “bad”. I recently moved to Virginia, but the library is even further away and also has limited material because it’s in a small, rural, conservative town. I would appreciate the opportunity to read books including the people in my community.” — 14, Virginia

- “Libraries are important to me because as a chronically ill person I’ve never been able to do the same things others my age were doing. My grandfather would take me to the library every other day in the summer and I would pick books to absorb myself in and distract myself from the reality of my situation. As I got somewhat older, I expanded my reading to different topics and I learned about different cultures and religions and realized how much toxicity their is in my family and background and Id like to think I’m taking the steps to break the cycle.” — 18, New Mexico

- “I read an honestly ridiculous amount. I’m applying because my parents aren’t often willing to drive me to the library, and while my school’s library is great, a) it’s a high school library, and b) I’m limited by the amount of books I can carry home in my backpack or in my arms, because I live in the fun little area where I’m technically close enough to walk to school IF I was fully abled, not on a time crunch, and not carrying a large backpack, so the school doesn’t provide busing and my parents won’t drive me.” — 14, Pennsylvania

- “I live in California, but I’ve experienced my dad say so many anti-LGBTQ and racist things. I think he would be upset if I brought a book home that didn’t align with his beliefs. I unfortunately can’t afford to live on my own, but I’d still like to read whatever I want.” — 21, California

- “Banned books are becoming a greater part of Texas education every single day, restricting students access to literature about sexuality and race. Groups of Texas parents putting pressure on districts to rifle through and take out each and every book relating to these topics. Unlike the majority of students in Texas, I attend on online magnet school. There are many advantages and disadvantages to the school, and unfortunately because everything is monitored, the censorship is even more extreme. Student’s are not allowed to discuss topics deemed ‘unfit’ in class and access to literature relating to topics as described above is highly restricted. As an LGBTQ+ identifying student, I find it really disheartening that topics relating to the life I live are ‘unacceptable.’” — 16, Texas

- “These kids we’re hiding these topics from, are going to be the ones running our state, country, and even planet. What’s it worth to hide what’s really going on in the real world?” — 13, Idaho

- “Well I don’t what else to tell you but I live in Oklahoma and it is very difficult for me to stay sane being a queer latinx teen, I’ve always felt frowned upon not only by white people (for being latinx) but also from my own family (for being queer) so only until very recently I’ve been discovering more queer latinx authors and I just, I feel so relieved that I’m not alone and that people share my experience.” — Oklahoma

- “I am unable to find these books at libraries, and I wish to keep the fact that I am reading these books private.” — 14, Wisconsin

- “[A]lthough the restrictions on access to books is not as bad here as say in Florida, it is very difficult to find books that represent my heritage (latino) and my family (LGBTQ). My school librarian works very hard to find current books that are diverse, but many times she is not allowed to purchase books that are considered “inappropriate.” I would like to have the chance to read more stories that show characters that are like my family. The public library is not much better, especially for young adult or general fiction titles.” — 18, Kentucky

- “I am 15 and live in Texas and while I haven’t really had any problems yet in community or school library (if you could even call it that, it’s very sad) but my problems are more at home. My parents are very religious and I had borrowed a few books from a friend but they literally threw them in the garbage even though they weren’t even theirs to throw away. I have a kindle tho and they seem to not really get it or view it as a risk compared to physical books? Idk it’s weird? My English teacher also lately has been bringing up when book bans are in the news and sounds like she supports them which I think is weird for an English teacher.” — 15, Texas

- “Looking at the ALA banned book lists from the past two years, I do not see a singular book that did not help me to better understand myself and my identities as well as the world around me. While I am privileged to live in a metropolitan area, I am queer and disabled and Jewish in a red state. I am constantly seeking to understand my own experiences and those of others through books, and I think I am a better and kinder person for it. These books did not make me the way I am, but they helped me to understand these identities more fully.” — 19, Georgia

- “This card gives me access to queer books as well as a huge variety of other books I can’t get through my small town library.” — 17, Idaho

- “My local library is currently being run by an unqualified mayoral appointee (not the usual way library directors are hired in our town) who keeps removing books from shelves with no due process. She has also been publicly called out for spewing racist vitriol on her social media.” — 13, Alaska

As of August 2024, the Brooklyn Public Library has seen nearly 9,300 eCard applications as part of the Books Unbanned program. Over 7,500 applications were completed, including more than 3,300 card renewals. Close to 4,700 of those cards are active, meaning they’ve been used to borrow material, and as of April 2024, 271,000 items have been accessed. Per capita, Oregon, Vermont, Utah, Nebraska, and Maine topped the list for most number of card applications per 100,000 in population.

Book Censorship News: September 20, 2024

- More than 100 children’s books with LGBTQ+ themes have been “suppressed”—banned—in Pasco Public Libraries while they’re reviewed. This came from a county commissioner complaint.

- Seven books were banned from Rockingham County Schools (VA).

- “Plass’s proposal would move adult content books to a lockable room, closet or cabinet that would be away from the public view. People 18 years or older would be given an Adult Access library card. In order to check out books in the Adult Access Only areas, patrons would request and check out a key at the front desk. A key log would be recorded to see when the key was checked out and returned.” This is in Northern Idaho, as if the state has not already ruined the public libraries enough. This proposal comes from a library trustee.

- Cobb County (GA) teachers are nervous about teaching this year as the district goes on a book banning spree.

- Columbia County (GA) public libraries are being forced to reshelve books in the collection after the county board of commissioners decided some were “inappropriate.” Now several YA books are in the adult section. It’s still censorship.

- Ashland Public Library (OR) is now being forced to remove a Pride banner that’s been on display.

- “Effective October 1, Atmore Public Library’s (APL’s) downstairs section will be for adults only. In a manner of speaking. On that date, in an effort to meet the most recent guidelines of the Alabama Public Library Service (APLS), no one under the age of 18 will be able to check out any book, video or other form of media from the local library unless a parent or guardian is present to OK the transaction, or a signed consent form is on file that gives the juvenile permission to borrow any item available for checkout.” Another adults-only public library.

- Authors talk about the real-world cost of book bans.

- How much did Utah spend on book bans? Two school districts alone had a combined cost of over $29,000. If they don’t suck the money out with vouchers, it’s through book bans. I’ve said that since 2021.

- “In Corpus Christi, the conservative-majority public library board recommended policy changes to restrict minors from certain content without parental input, remove references to diversity and the freedom to read, and make it easier to challenge books.” This is the public library.

- In Grafton, West Virginia, “concerned citizens” are mad about books for sale at a local bookstore. Remember it’s not “just” books on shelves in schools.

- Prince William County Schools (VA) are implementing new book “parental control” systems after a made up controversy over a book.

- The lawsuit Moms For Liberty filed against Clyde-Savannah Junior-Senior High (NY) is moving to the Albany County Supreme Court.

- “After a year of controversy over LGBTQ book displays, county commissioners in a small North Carolina town began proceedings to withdraw their public library from the regional system, a move that threatens vital services and state funding. But some residents are organizing to prevent the change.” This is Yancey County Public Library in North Carolina.

- Billings Public Schools (MT) are debating what their library policies should be in light of new laws. Nice quote from a parent who wants to change the definition of “obscenity.” The new policy did not pass.

- The latest update on the lawsuit filed against the Prattville Public Library (AL) board.

- Here’s where and how books are being banned throughout Tennessee.

- This story offers actual little information, in part because it sounds like the school district is not being forthcoming with information, either. Watertown Schools (NY) are in the process of removing 47 books. But the books listed look to be the kinds that would be legitimately weeded from a library—the story kind of touches on that but then throws in a line about Sarah J. Maas’s oft-banned book.

- Greenville County Schools (SC) are claiming that it’s the new state restrictions on books that is the reason they canceled school book fairs. Can’t wait to see them pull in the right-wing book fairs as a “compromise.”

- Book banners are staging a “press conference” to talk about how they want to get more books banned in Cobb County, Georgia, schools.

- After banning or relocated several books that parents complained about, Lake Travis Independent School District (TX) has now given parents the feature to restrict any books they’d like from their students.

- Following complaints about a textbook in Johnston Schools (IA), it’s been approved. Story is paywalled for me.

- Also paywalled for me is this story about the ACLU warning Rutherford schools (TN) not to pull books like The Bluest Eye from shelves.

- In “what a great use of taxpayer money,” the Florida Attorney General’s office will be going to the hearing on the Texas federal lawsuit over HB900 (aka, the book banning law). Wonder why?

- Oregon had a record number of book ban requests last school year. That’s the trend nearly everywhere.

- “The Francis Howell school board on Thursday will vote on a policy amendment that would allow hate speech, false science and false historical claims in educational materials. The change would reverse a vote the board took in August that banned such content.” This particular Missouri school is being decimated by its board.

Let’s end with one bright spot: Samuels Public Library, which you may remember from the near-closure of the facility at the hands of a small, vocal group of bigots, was named Virginia’s Library of the Year.

Print

Print