A summer heat wave had once again sped up the harvest in the Golden Triangle, a mostly flat, fertile pocket of land in Montana’s northern plains. In early August, Jon Tester, the state’s third-term senator, was home, at the end of a long unpaved road, tending to his wheat. Tester calls himself the only “working dirt farmer” in the Senate, and despite his critics’ belief that this is mostly performance, he does, in fact, continue to till the soil near the town of Big Sandy, where he has lived his entire life—and which his grandparents settled in following the Homestead Act of 1862, a giveaway of Indigenous land. Tester and his wife, Sharla, had recently bought some additional acres from their neighbors, Verlin and Patty Reichelt. “I just talked to him this morning next to his tractor,” Verlin told me. The Reichelts are recently retired wheat farmers and, like the Testers, part of a vanishing clan of rural Democrats.

When I met the Reichelts for a drink at the Mint Bar and Café, one of the few storefronts in Big Sandy, and asked if they felt comfortable talking on the record, Patty said, “I’m tired of being off the record! I’m so tired of Republicans saying that the Democrats are going to take the guns away.” She pulled out a little card she’d laminated, listing thirty-one priorities the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 suggested for a second Trump term: “Cut Medicare”; “End marriage equality”; “Deregulate big business and the oil industry.” She wanted to be out and proud as an MSNBC liberal, and was feeling good about the burgeoning energy around Kamala Harris and Tim Walz. But when a man in a Trump shirt (“WE’RE TAKING AMERICA BACK”) walked in a few minutes later, and received a compliment from someone at another table, she lowered her voice.

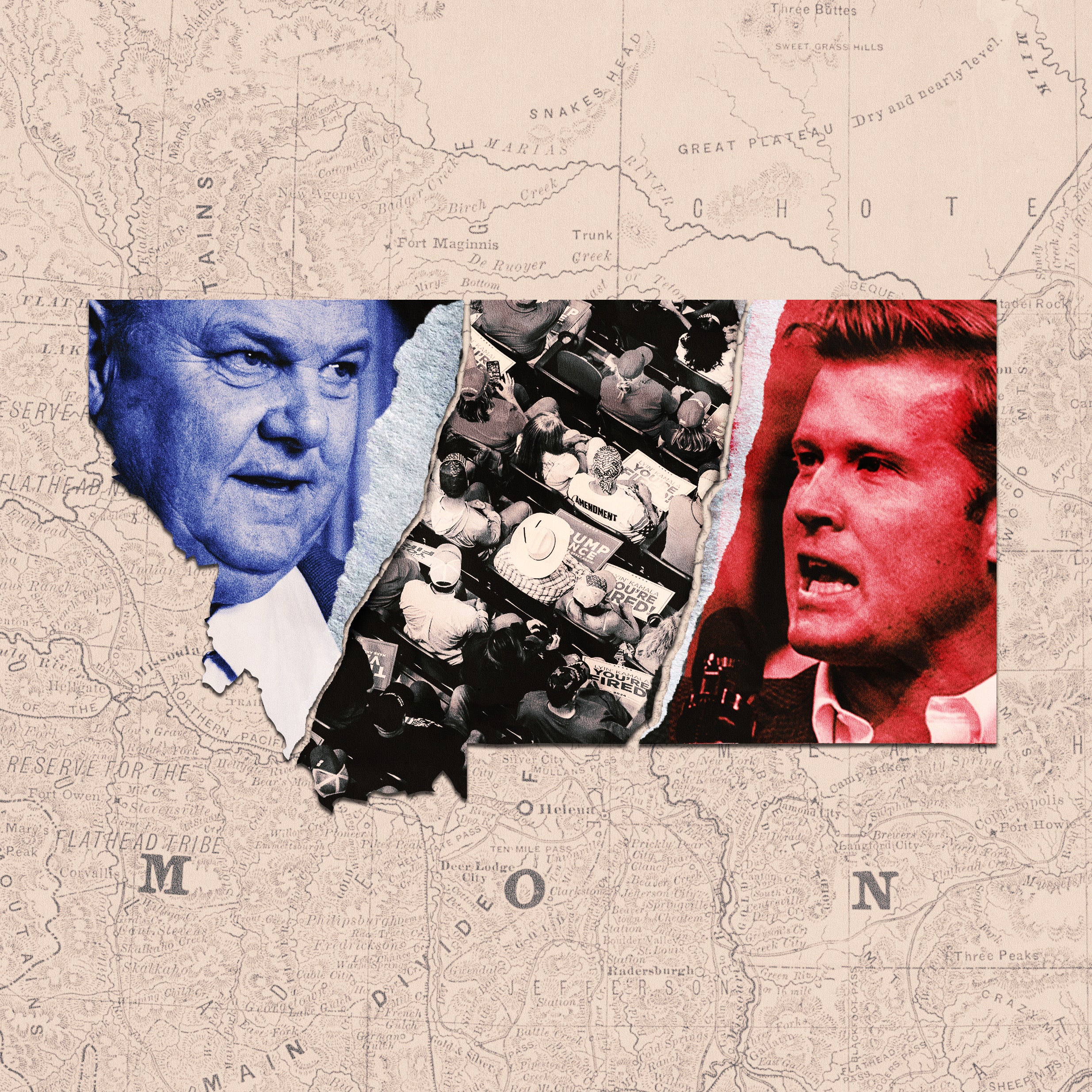

The previous evening, in Bozeman—which has come to be known as “Boz Angeles,” especially after an influx of pandemic-era digital nomads, and where the median price for a home is nearly eight hundred thousand dollars—I’d watched fans of Donald Trump pack the arena at Montana State University. There were toddlers in stars-and-stripes onesies and girls in bedazzled cowboy boots. Bozeman, like Billings and Missoula, tends to vote Democratic, but it has produced a number of prominent Republicans. Trump was preceded onstage by a home-town lineup: Governor Greg Gianforte, Congressman Ryan Zinke, Senator Steve Daines, and candidate Tim Sheehy, the young, blond former Navy SEAL who is trying to unseat Tester and join the ranks of rich guys from Bozeman at the top of Montana politics. It was a big-bellied, masculine affair. The only women to take the stage performed ceremonial roles: Miss Montana, Kaylee Wolfensberger, sang the national anthem; Christi Jacobsen, the secretary of state, led the Pledge of Allegiance.

Trump finally appeared around nine-thirty. His plane had been rerouted to Billings, a long drive away. “I gotta like Tim Sheehy a lot to be here,” he said. “He better win.” Trump himself will certainly win Montana by double digits, as he did in 2016 and 2020. His presence indicated both the importance of the Senate race and his lingering dislike of Tester, with whom he has an old quarrel. In 2018, Tester had blocked Trump from appointing his former White House physician Ronny Jackson to run the Department of Veterans Affairs. Trump and his son Donald, Jr., responded by making repeat trips to Montana to campaign against Tester. At the recent rally in Bozeman, Trump brought Jackson onstage to call Tester “a sleazy, disgusting, swamp politician.”

Only around a million people live in the entire state, yet, come November, Montana could well determine the balance of power in the U.S. Senate. There are other critical races—in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Nevada, Wisconsin, and Arizona—but the Democratic candidates in those places are ahead in most polls. Republicans need to flip just two seats this year to reclaim control of the chamber. In West Virginia, where Joe Manchin is not seeking reëlection, a G.O.P. pickup is assured. And in Montana, where public opinion can be scattered and hard to gauge, Tester has lately seemed to be falling behind Sheehy.

Until somewhat recently, Montanans cast mixed ballots that painted the state a blurry wash of purple. But in the past decade, and particularly since 2020, rural Montana, once shaded New Deal blue, has gone MAGA red. (Smaller cities and Indian reservations are split.) At the same time, national politics have displaced local: national campaign money, national broadcast media, and national culture wars. Tester is the last Senate Democrat in a red, rural state, and one of the only congressional Democrats left in the northern swath of America stretching from Seattle to Minneapolis.

Though he has pulled out many unlikely wins, this election is his first on the same ballot as Trump. “I’m sure it’ll matter,” Monica Lindeen, a Democrat who served in the statehouse and as state auditor, told me. “Voting patterns in the state have definitely become more conservative.” The Montanans whom Tester managed to attract in previous cycles either belonged to a kind of F.D.R.-era coalition (metropolitan liberals, union members, Native Americans, conservationists, farmers reliant on subsidies, ranchers on public lands) or were libertarians or Republicans who simply liked him, despite his party affiliation. He has always played up his bipartisanship, rooted in an understanding of “Montana values.” But this year, in the glare of the Presidential race, he has started to sound more like a Republican. Or maybe that’s just what it means, these days, to be a rural Democrat.

Trump’s popularity with Montanans means that any Democrat running for statewide office there needs to pull in MAGA voters. One way to accomplish this is to create some separation between Party and self. In mid-July, Tester, who’s sixty-eight years old, became the second Senate Democrat to publicly break with Joe Biden and call on him not to run for reëlection. (A nonpartisan poll in March showed Tester slightly ahead of Sheehy, while Biden trailed Trump by twenty-one points in the state.) Tester declined to support Harris and Walz before the Democratic National Convention and then skipped out on the Convention altogether. He went to Missoula instead, to do a campaign event with Jeff Ament, the bassist for Pearl Jam, before a big concert. Ament grew up in Big Sandy and played in childhood basketball games that Tester refereed. His father was the town’s mayor and gave Tester his first flattop haircut.

When Tester first arrived in Washington, in 2007, after defeating a Republican incumbent, his profile as a seven-fingered farmer (meat-grinding accident), a former public-school music teacher (aspiring saxophonist turned trumpeter, following the meat-grinding accident), and a Democratic senator from a rural state made him unusual, though not nearly as unusual as he is today. His cohort included other non-coastal, centrist Democrats such as Claire McCaskill, of Missouri, and Sherrod Brown, of Ohio. McCaskill was voted out in 2018, and Brown is currently facing a difficult reëlection battle.

In June, I attended a hearing of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, which Tester chairs. The committee was reviewing budget requests for the Reserves and National Guard. A few members of CodePink, the pacifist group, held up their hands, painted red, to protest U.S. support for Israel in its war on Gaza. Other than that, the hearing was dull, an Excel spreadsheet come to life. Tester has made the military, and veterans’ issues in particular, a focus of his career. In Montana, which has one of the highest proportions of veterans of any state in the U.S., he has secured funding for new V.A. clinics and expanded access to mental-health care; his PACT Act addresses the fallout from toxic exposures encountered in the line of duty.

I caught up with Tester after the hearing, for a fifteen-minute interview. (“In Washington, my daily schedules are broken down into fifteen-minute increments in order to accommodate as many meetings as possible,” he writes in “Grounded,” his 2020 memoir.) He wore a black suit and an orange-striped tie. He sank his big frame into an armchair; his face formed a trapezoid under his signature flattop. Congress had not been especially productive in recent months. We had just heard officials from the Reserves and National Guard testify about delayed budgets and the urgent need for equipment. A comprehensive farm bill was stuck. There was no movement on a solution to the border crisis, which is talked about constantly in Montana, though only two per cent of the population is foreign-born. Tester had joined up with forty-six Republicans to co-sponsor an “immigrant crime” bill, and he opposed the Biden Administration’s attempt to establish minimum-staffing quotas in nursing homes. The quota “is a prime example of a one-size-doesn’t-fit-all policy coming out of Washington, D.C.,” he told me. “We don’t have enough doctors and nurses in Montana.”

When I asked what the highlights of the legislative session had been, he sighed. “Not unlike previous sessions, I really don’t think about what we’ve done, because we’re more focussed on what has to be done,” he said. “During my time here, we’ve lost a lot of folks in the middle. You try to find common ground. Like, on the farm bill, you agree on something and put it on the floor, let the committee fix the problems.” He went on, “Then the people know you’re working. They’re thinking this place is totally screwed up, which it is.”

Tester flies back to Montana nearly every weekend, and maintains the public persona, and social-media accounts, of a small-town farmer or mechanic, the kind of guy every Montanan used to know. “He’s always been this very open, personable, funny guy, which I think has been one of the reasons why he continues to win,” Mike Dennison, a veteran reporter in the state, told me. “This campaign, I am surprised at how much he is completely running away from Democrats and not stopping and saying, ‘Here are the things that Democrats have done that are good for Montana, such as the infrastructure bill and hundreds of millions of dollars for the expansion of broadband.’ ” (When I asked Tester’s campaign about this, no one would respond directly, but they said that he has not shied away from touting these accomplishments.)

While Tester goes it alone, his opponent has hewed close to the national Party. Sheehy is in his late thirties and new to politics. He grew up in Minnesota—Tester’s campaign calls him an “out of stater”—but now presents as thoroughly Mountain West. He writes in his memoir, “Mudslingers,” that the 9/11 attacks spurred him to join the military. He attended the U.S. Naval Academy, where he met his future wife, Carmen, then became a Navy SEAL and was deployed to numerous conflict zones. About a decade ago, he retired from the armed forces, bought ranchland near Bozeman, and started Bridger Aerospace, an aerial-firefighting company that contracts with government agencies to put out wildfires, which have been intensified by climate change. (Sheehy has described climate change as “neither a fantasy nor merely a political tool.”) Watching America’s messy withdrawal from Afghanistan, in 2021, he grew angry and motivated. “That’s when I called Ryan Zinke, Steve Daines, the Governor, and said, ‘Whatever I can do, I have a personal vendetta against this Administration, old F.J.B.”—Failing Joe Biden—“over there and all his lackeys, who include that stupid, two-faced Tester,” he recalled at a fund-raising dinner in April.

Senior Republicans were happy to oblige, and saw in him a capable, if untested, politician. (Zinke, also a former Navy SEAL, had presented Sheehy with a Purple Heart, in 2015.) Daines, who chairs the National Republican Senatorial Committee, helped to clear the Senate-primary field of other G.O.P. aspirants, including Matt Rosendale, the Montana congressman who’d lost to Tester in 2018. “Tim Sheehy is in a strong position to win this seat,” Daines told me. “He’s got a business background. He’s a very accomplished rancher, too. I thought he’d make an outstanding senator. I know talent when I see it.”

The version of Sheehy represented in “Mudslingers” is moderate: an earnest public servant concerned with climate change and the excesses of America’s “forever wars”; someone who believes in multiculturalism and is “all about equality, inclusion, maternity leave, and other fundamental rights.” Sheehy has since adopted a more conservative, combative identity, in keeping with Trump and the evangelicals in Montana’s Republican Party. He casts Tester as a sold-out career politician who answers to “D.C. special interests.” At the rally in Bozeman, Sheehy repeated a joke he’d made during a speech at the Republican National Convention. “Well, you know my name. Did you know those are also my pronouns? I’ve been a ‘he-she’ for thirty-eight years,” he said.

In ads, Tester-allied groups call him “Shady Sheehy.” As first reported by the Washington Post, Sheehy has offered conflicting accounts about a bullet wound in his right arm, which was either incurred during combat in Afghanistan or accidentally while he was visiting Glacier National Park with his family. Sheehy would not speak with me, nor did his campaign respond to requests for comment, but he has said that the gunshot may have been a product of friendly fire and that he decided not to report it to the Navy, and later lied to a park ranger about its origin, in order to protect members of his platoon. (A Navy spokesperson sent me a copy of Sheehy’s service record but would not otherwise comment.) Then there’s the question of whether Bridger Aerospace is wildly profitable, as he has claimed, or badly in the red, as recent S.E.C. filings show. Sheehy contends that the business model is inherently volatile, depending on the availability of government contracts. Bridger reported to the S.E.C. that its “operating results are impacted by seasonality” and “fluctuate significantly from quarter to quarter and year to year.”

Ask Republican voters what they make of all this, and they seem unfazed. Marvin Kimmet, who runs his family’s cattle ranch and the Republican county committee near Glacier National Park, told me that he’d met Sheehy in person and concluded that the bullet-wound controversy is “more bullshit than substance.” Nor did it bother him that Sheehy was originally from Minnesota. Sheehy had Trump’s endorsement, and the Republicans needed to retake the Senate—the national math was clear. In any case, Kimmet had never voted for Tester. He opposed the senator’s support for the Affordable Care Act and the Biden Administration’s “green ideas,” which were out of synch with local interests. “I knew Jon Tester when he was in the statehouse, enough to say hello and drink a beer with him,” Kimmet told me. “But Washington puts a different aspect on their political careers.”

Summer is a time of fairs, parades, and powwows across the state, and in an election year these events double as campaign stops. Tester rode a tractor in the Fourth of July parade in Butte. Sheehy posed with his dirt-covered children at a rodeo in White Sulphur Springs. The morning after the Trump rally, I drove to Basin, a mining town turned countercultural refuge (artists, radon-therapy seekers), for its annual Basin Days festival. On the short main street, the crowd and politics were mixed. I spotted signs for Tester, Sheehy, and Trump near the booth of a prayer club and a pink coffee truck. A long-shot Democrat running for the state House of Representatives sat under a tent and greeted passersby; across the street, a saloon served Caesar salads in plastic cups, garnished with pickled asparagus.

Stu Goodner and his wife, Lisa, who live on twenty acres in the nearby mountains, came in matching plaid shirts, hats, and sunglasses. Goodner, who is the chair of the Jefferson County Republican Central Committee, was handing out flyers for a fall harvest festival where a “One of a Kind Glock 17 9 mm” etched with a stars-and-stripes design would be raffled off. “My grandparents were dyed-in-the-wool Democrats,” he told me. “That was an era when it was the working man against big business. I believe the Democratic Party got away from that base into more of a special-interest-type base.” Goodner saw the Senate race as a chance to rebuke coastal liberalism. “It’s over ninety per cent that Tester voted with Biden,” he said. “And Biden’s policies, therefore, are his policies.”

Though Sheehy has raised roughly a third of Tester’s forty-four million dollars, he enjoys certain built-in advantages: voter loyalty to Trump and a Party infrastructure nurtured by activists like Goodner. I wondered if Sheehy’s popularity would suffer when, in late August, the Char-Koosta News, an online outlet based on Montana’s Flathead Reservation, published audio clips of him at two separate events in 2023, mocking Native Americans for being “drunk at 8 A.M.” (More than six per cent of the state’s population is Indigenous.) But two weeks later the Cook Political Report changed its prediction in the race from “tossup” to “lean Republican.” The Montana Democrats, meanwhile, are in the process of rebuilding after wipeouts in the past two election cycles. In 2020, they lost the governor’s seat, which they’d held for sixteen years; in 2022, Republicans won a bicameral supermajority. With the help of recent redistricting, the Democrats hope to regain some ground, and to deliver victories for Tester, the gubernatorial candidate Ryan Busse, and the Zinke challenger Monica Tranel.

Pro-choice enthusiasm could be essential. A ballot initiative in November will ask voters whether to codify the right to abortion in the state constitution. “Tester probably knew he needed to have an abortion measure on the ballot with him,” Jessi Bennion, a political scientist at Montana State University, told me. “In other states, it’s been a boon to Dems. It brings out a highly motivated kind of voter and brings in the suburban woman voter.” (Nine other states will vote on abortion initiatives in November.)

One evening in Great Falls, a swing city on the edge of the Golden Triangle, I visited with Helena Lovick, the chair of the local Democratic Party, and Ken Toole, the retired head of a human-rights nonprofit and a former state senator. They had recently helped to start a blog called What the Funk 406 (the statewide area code), in response to the lack of political reporting in Great Falls, whose venerable newspaper, the Great Falls Tribune, is down to a very small team. The decline of local media, Toole told me, had produced a more hermetic citizenry and more extreme elected officials. It had also meant that local politics were becoming nationalized: Fox and, to a lesser extent, MSNBC, were torquing the concerns of Montanans to fit prefab ideologies.

Lovick had spent that afternoon at Tester’s campaign office, preparing four dozen volunteers to go canvassing. She was feeling optimistic, and hoped that the Montana Democrats would take pride in their platform rather than pander to the MAGA set. “Why be Republican-lite? They’ll just vote for a Republican. I’ve seen some candidates locally try to play that game, and it’s just doomed to failure,” she told me.

The Tester campaign had just unveiled Republicans for Tester, an endorsement effort by more than a hundred Party members across the state, including Marc Racicot, a former governor who later served as the head of the Republican National Committee and a campaign lead for George W. Bush. At a Missoula coffee shop, I met Tranel, a lifelong Montanan and a trial lawyer who’s running against Zinke for a second time in the state’s western congressional district. The race had been so close in 2022 that the national Democrats announced that they would invest extra resources in her current campaign. Yet Tranel told me that she identifies only as herself, not with the Party. “My work this cycle is to really get in front of as many conservative, independent voters as I can and say, ‘Here’s who I am, here’s what I’m about,’ ” she said.

Tester, too, had cultivated his Testerness—and a centrist appearance—to make it this far. But as Toole, the former state senator, told me, “If you look at his voting record, he’s no Joe Manchin. He knows which team he’s on.” That team, in Montana, once had many players. “Now Jon’s the only one left standing.” ♦