In advance of Tuesday night’s Presidential debate, which will be held at the National Constitution Center, in Philadelphia, Kamala Harris and Donald Trump have been fleshing out their economic agendas. Although there are a few areas of common ground—they both want to block the sale of U.S. Steel to a Japanese company, for instance—the choice facing voters could hardly be starker.

Harris is presenting herself as a forward-looking progressive pragmatist who recognizes the importance of creating wealth as well as sharing it more equally. Last week, in New Hampshire, she promised to expand tax breaks for small businesses and held up a vision of an “opportunity economy” in which “everyone, regardless of who they are or where they start, can build wealth, including intergenerational wealth.” Trump, meanwhile, is portraying himself as the heir to a Republican President who occupied the White House more than a hundred and twenty years ago: William McKinley.

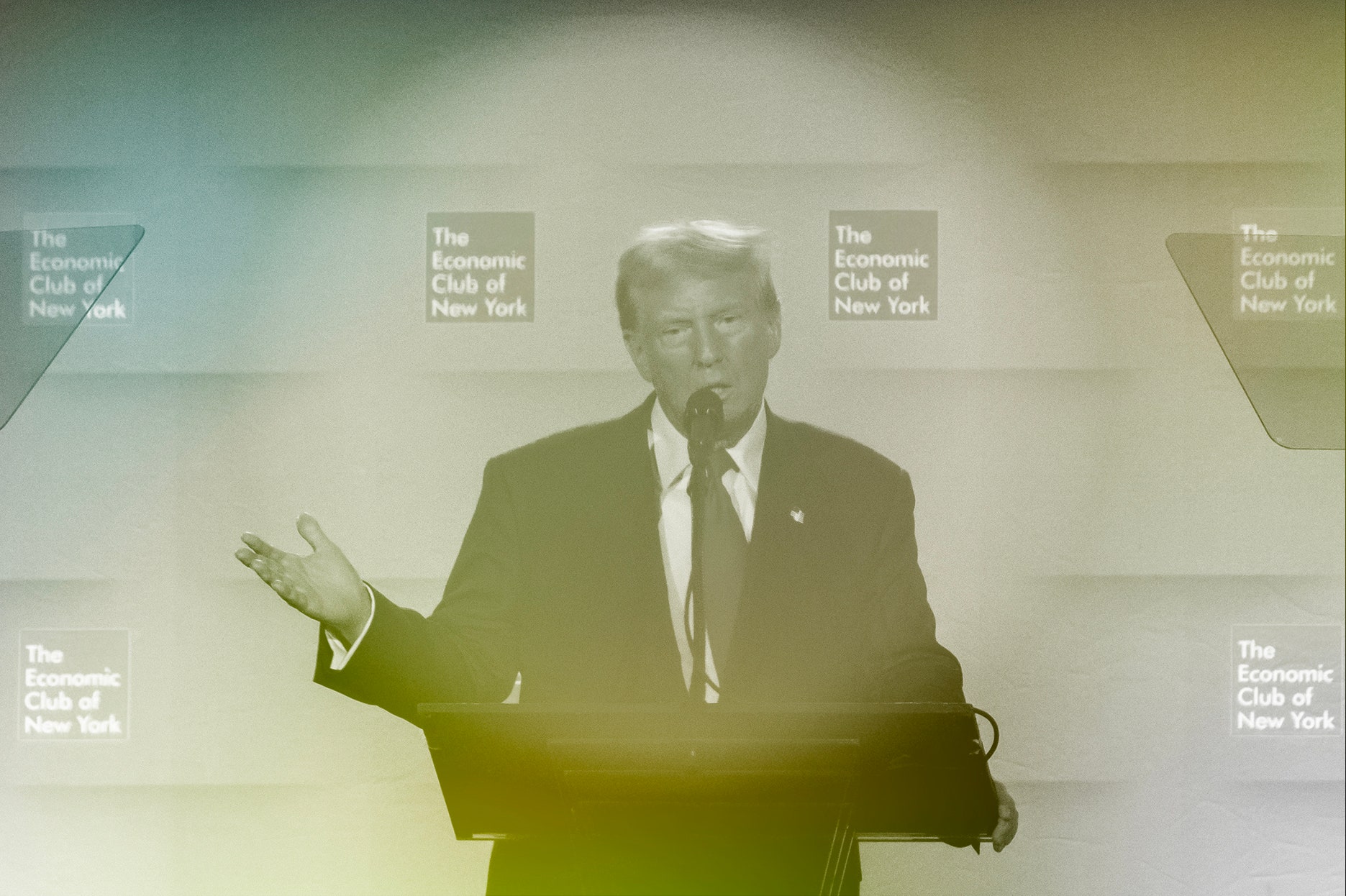

In an address to the Economic Club of New York, on Thursday, Trump hailed the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890, which McKinley proposed when he was a congressman, and which drastically raised the duties payable on many imported goods. As President, from 1897 to 1901, McKinley continued protecting domestic manufacturing, signing another tariff-hiking piece of legislation. In this spirit, Trump quoted him as saying that Republican tariffs had “made the lives of our countrymen sweeter and brighter.” He went on to argue that his own proposals for blanket tariffs—ten per cent on all imports, and up to sixty per cent on goods from China—would transform the American economy.

History isn’t the only dividing line, of course; taxes and economic fairness are another one. In his speech, Trump raised his campaign’s opening tax bid, which was a pledge to extend all the giveaways to businesses, investors, and high earners that were enacted in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. Among the provisions in that bill was a whopping reduction in the corporate tax rate, from thirty-five per cent to twenty-one per cent. Trump pledged to cut the rate even further, to fifteen per cent, for businesses that make products in the United States.

Harris, in contrast, has pledged to raise to twenty-eight per cent both the corporate tax rate and the tax on long-term capital gains for households that earn more than a million dollars. The first proposal is in line with what the Biden Administration has advocated. The latter one is a reduction: the Administration has called for a capital-gains tax rate as high as 39.6 per cent. Harris’s twenty-eight-per-cent rate, however, would be levied alongside a separate investment tax of five per cent, which would bring the combined rate to thirty-three per cent. So, “the all-in top capital-gains rate would be the highest since 1978,” the Wall Street Journal noted.

The Harris campaign has also indicated that it supports another Biden proposal, to impose a minimum effective tax rate of twenty-five per cent on the annual incomes of households worth more than a hundred million dollars, including unrealized capital gains on their wealth. (According to one recent estimate, there are roughly ten thousand such households in the United States.) Enacting this measure would involve some practical challenges, including creating rules for the valuation of non-traded assets that rich people own, such as art works. But, at least in theory, the new levy would expand the federal tax base, something that is sorely needed given the rising burden of the national debt, and fulfill the longtime progressive goal of taxing huge fortunes that largely escape the clutches of the I.R.S. because of quirks in the tax code that favor the rich, such as the “step-up in basis” loophole for inheritances.

As a proud member of the plutocracy, Trump has dismissed taxing unrealized wealth as the “craziest idea.” But how would he pay for his expansive tax cuts and breaks, which, according to Bloomberg News, could cost a stunning $10.5 trillion over the coming decade? At the Economic Club, Trump said that he would appoint a government commission, led by Elon Musk, to identify “trillions” of dollars in government waste. History suggests that such exercises rarely have much impact on the trajectory of spending. And, as Bloomberg noted, “Even if Congress were to eliminate every dollar of non-defense discretionary spending—projected to be $9.8 trillion over the next 10 years—it still wouldn’t offset the estimated expense of the wide-ranging tax cuts Trump and Vance have floated in recent weeks.”

Trump’s message is, Never fear. His tax cuts and new tariffs will create so much economic growth, and generate so much extra tax revenue, that everything will be tickety-boo. In response to a question about the budget deficit from John Paulson, the Republican donor and hedge-fund billionaire, Trump said, “We’re gonna grow like nobody’s ever grown before.” When Reshma Saujani, the founder of Girls Who Code, asked him if he would prioritize legislation to make child care affordable, his answer was so evasive and rambling that it was difficult to follow. Close inspection revealed that he had suggested his tariffs would bring in enough money to “take care” of everything, including expanding child care. The combination of tariffs, tax cuts, and reducing waste would have such a transformative effect, Trump said, that “I look forward to having no deficits within a fairly short period of time.”

This is truly the “craziest idea.” A ten-per-cent tariff levied on all $3.8 trillion of U.S. imports could theoretically raise three hundred and eighty billion dollars. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the 2024 budget deficit will be $1.9 trillion—five times as much. In 1980, George H. W. Bush famously described Ronald Reagan’s claim that large tax cuts for the rich would pay for themselves as “voodoo economics.” More than four decades on, Trump is making claims that would have made Reagan blush, especially since the Californian conservative was a staunch supporter of free trade. (In 1979, more than a decade before NAFTA, he proposed a North American trade accord between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico.)

Nobody can say for sure what impact Trump’s new tariffs would have over the long term. But virtually by definition, they would raise prices and reduce consumers’ spending power. That would negatively affect economic growth in a manner that could well outweigh the stimulative impact of more tax cuts. “We estimate that if Trump wins in a sweep or with divided government, the hit to growth from tariffs and tighter immigration policy would outweigh the positive fiscal impulse,” economists at Goldman Sachs wrote last week.

The tariffs that Trump is proposing are much broader and more indiscriminate than the ones he introduced in his first term. When he spoke to the Economic Club in 2016, he promised to target countries, principally China, that had manipulated their currencies and adopted other unfair trading practices. After Trump was elected, his Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, released a lengthy report detailing China’s alleged infractions, which formed the basis of the duties—fifty billion dollars initially, later expanded to three hundred and fifty billion—that Trump imposed on Chinese goods. Significantly, the Biden Administration left those tariffs in place, and, earlier this year, it added to them, with new duties on Chinese electric vehicles, batteries for those vehicles, semiconductors, and medical supplies.

Trump is threatening to impose tariffs on all imports, regardless of their origin. If he followed through on this pledge, it would surely lead to retaliation by other countries, which could ultimately lead to a global trade war. For the United States, as the world’s biggest economy, and its second-largest exporter, that would be a self-defeating outcome. When, during the late nineteenth century, McKinley and other Republicans embraced comprehensive protectionism, the country was still transitioning from agriculture to industry, and the Northern industrialists who bankrolled the G.O.P. were intent on building up their businesses behind high tariff walls. But even McKinley eventually conceded that such a policy didn’t make sense for a mature industrial economy. On September 5, 1901, the day before he was assassinated by an anarchist, he attended an exposition in Buffalo, where he said, “Commercial wars are unprofitable. A policy of good will and friendly trade relations will prevent reprisals.” Evidently, McKinley’s last speech hasn’t made it onto Trump’s reading list. ♦